The Limit to The Limits of Knowledge.

Why Hayek’s knowledge problem fails practically as a critique of technocracy.

Over the last half-century-or-so, many democracies, including the USA, the UK, and Japan, have made their central banks ‘independent’ of political control, meaning that that central bankers are no longer bound by the elected administration’s priorities and projects and are accorded the authority to fulfil their various mandates – such as fixing short-term interest rates or regulating commercial banks – at their own discretion.

Broadly speaking, this ‘independence’ has two rationales: deference to technical competence and the elimination of perverse incentives. Central banks are expected to stabilise the national economy by intervening in a ‘counter-cyclical’ fashion (that is, by countering inflationary and recessionary pressures with an increase or decrease of short-term interest rates, respectively) which, it is felt, requires macroeconomic expertise and being free of an election-cycle’s perverse incentive to avoid unpopular but necessary deflationary policies. Central bankers, many of whom held PhDs in economics or some sister discipline, had a claim to the former; independence granted them the latter. In the words of Allan Sproul, one-time president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, monetary policy was made dependent on “the discipline of competent and responsible men”.1

In this way, post-independence central bankers are archetypical technocrats. Unlike democratically-elected ministers and their plutocratic donors who draw on ‘The Will of The People’ or their immense wealth respectively to design and set social policy, central bankers’ authority over the shape of monetary policy is fundamentally rooted in their capacity to mobilise, produce, and interpret highly complex macroeconomic information. As such, their – or indeed any technocrat’s – exercise of power can be roughly divided into two parts:2

Setting the terms of a policy discussion by mobilising, producing, or interpreting highly complex technical information to make sense of a particular domain of policy intervention.3

Deciding how to intervene into the policy domain in question, in this case ‘The Economy’.

Now, given that it is the first of these that effectively distinguishes technocracy from other forms of policy-making (e.g., democratic or plutocratic ones), most critiques of technocracy aim to challenge technocrats’ competence by pointing to the limits of technical knowledge.4 Technocrats, these arguments claim, should not be given the authority to shape policy because, for whatever reason, the technical information needed to do so always lies beyond their reach. Prominent amongst these arguments is Friedrich Hayek’s ‘knowledge problem’, which argues that technocrats (he focusses on central planners) can never gather the knowledge that they need to govern because it is always irreducibly dispersed across society.5 This is a well-known and very influential argument and, slipping momentarily into the autobiographical, lies at the heart of my worldview. I have been more or less convinced by Hayek’s theoretical and philosophical criticisms of technocratic knowledge claims, and have made use of them in my own modest attacks on technocratic policy.

The problem is that it is now no longer clear to me that the ‘knowledge problem’ actually presents a challenge to technocracy as I have laid it out here. That is, it is not clear to me whether, in practice, the knowledge argument actually challenges technocrats’ competence in making (i.e., doing 1) and governing on the basis of (i.e., doing 2) rarefied knowledge-claims. Instead, as I will show in this post, it only really challenges their competence in making and governing on the basis of certain kinds of knowledge claims about the world. I will do this using an example taken from Annelise Riles’ ethnographic work at the Bank of Japan, where she observed the central bankers articulating and then negotiating a ‘knowledge problem’-like criticism of their policy-making. Crucially, she describes how they very effectively assimilated the critique within their practice, without letting it fundamentally challenge either their privilege to make or govern on the basis of knowledge-claims. This, I will suggest, raises a pair of interesting, and potentially troubling, question for proponents of the ‘knowledge problem’ – does the argument, in fact, challenge the structure of technocracy? And, if not, is that a problem?

Before doing so, however, I need to say a bit more on the ‘Knowledge Problem’.

§ The 'Knowledge Problem’.

Hayek’s ‘knowledge problem’ is, in fact, Don Lavoie’s ‘knowledge problem’ (in that he baptised it) and is, in fact, two knowledge problems, both of which make the same point – namely, that the information needed to deliberately coordinate supply with demand/need for certain goods can never be available to a single, policy-making mind (or small group thereof) because it is always irreducibly dispersed throughout society.6

The first – and seminal – version of this argument appears in Hayek’s The Use of Knowledge in Society, in which he analyses the basic economic problem facing policy-makers and aspiring central planners, formally technocratic or otherwise…7 The problem, says Hayek, with policies that look to rationally organise (that is, to ‘centrally plan’) production and the distribution of goods produced is that they are predicated on “the utilization of knowledge which is not given to anyone in its totality”.8 The problem with policies that seek to dictate who produces what where, in an attempt to meet people’s needs and wants is that they depend on aggregating fundamentally unaggregatable knowledge about productive capacity (i.e., supply) and need/want (i.e., demand).

Hayek’s heirs apparent – Lavoie amongst them – developed this argument further, ultimately identifying two reasons why central planning depends on making impossible knowledge claims about the state of supply and demand, naming one ‘the complexity problem’ and the other ‘the contextuality problem’.9

Let’s briefly consider each in turn.

The complexity problem.

Knowledge about supply and demand is local, subjective, and diverse (or, in a word, complex), and this makes it prohibitively difficult to aggregate. Fundamentally, what we consider important or valuable depends on the particularities of our environments and personal dispositions. As our recent experience with COVID-19 illustrated, though they are both adult human males, a Hasidic Jew’s needs and demands are very different to those of an upper middle-class hypochondriac with a big garden and a well-stocked wine cellar… Detailed knowledge about how goods are produced is similarly diverse and invariably tied to the particularities of time-and-place. Even knowing how to profitably produce something as simple as a footstool implies having a rich, local understanding of who to get wood from, how to negotiate with them, how to wield wood-working tools, where to get paint from, how to paint, where and how to advertise his products, etcetera. And this has only gotten truer as our economies have grown denser and more global.

As such, the sheer complexity of supply/demand exceeds the computational limits that any technocrat could realistically hope to possess. The knowledge needed to competently plan out the distribution of goods and services across society is simply too complex to aggregate.10

The contextuality problem.

To my mind, a crucial difference between the complexity and the contextuality problem is that where the former focusses on the actual or practical prospect of knowledge aggregation, the latter attacks its in principle possibility. The complexity problem allows that under the right, hypothetical conditions, knowledge about supply and demand could be aggregated. In other words, the complexity problem allows that if time was infinite, energy superabundant, and computational power unlimited, then technocrats could successfully make knowledge claims that remain unmakeable in our world, where none of these conditions are met. By contrast, the contextuality problem argues that aggregation is always in-principle impossible, given the nature of human knowledge which, it argues, is primarily tacit, practical, and impossible to articulate (i.e., to convert into theory or proto-theory) exhaustively.

Now, there are about a thousand-and-one accounts of “tacit knowledge”, “know-how”, and “practical wisdom” peppering the annals of anthropology (e.g., Marshall Sahlins and James C. Scott), economics, (e.g., Friedrich Hayek and Don Lavoie), and philosophy (e.g., Hubert Dreyfus, Michael Polanyi, Gilbert Ryle, Charles Taylor, ad nauseam!) but their core implication is always broadly the same – that our knowledge of the world, of ourselves, and our place within it, depends on beliefs, rules, and practices that necessarily exceed our conscious grasp.11 Take the simple example of using a stepping-stone to hop across a stream. We are not usually able to articulate how we do it, to say how we place our foot or position our hands or hold our spines or angle our hips or swivel our eyes, and yet we all know how to do it when the world demands it of us. Perhaps counterintuitively, the reflections, articulations, abstractions, and scientific theories that occupy so much of our conscious lives represent only a sliver of human knowledge and exist against a background of tacit, practical, unconscious, or otherwise inarticulable knowledge.

This tacit/practical dimension has two implications that concern us here. The first is that much of human knowledge cannot be separated from the actual, real-world situations in which it finds expression (it is, in a word, ‘contextual’). Consider the example of the stepping stone once more. Since our knowledge of how to cross the river resists full articulation, it cannot be converted into an abstractly graspable (i.e., theoretical) form, extricable from its river-stone-and-human-agent context of expression. The second, and attendant, implication is that much of the knowledge needed to effectively administer to supply and demand is simply inaccessible to aspiring planners. Much crucial knowledge about what is needed, what matters, and how to make it is tacit/practical and therefore inseparable from its context of expression. More often than not, we are not perfectly conscious of what we do and why we do it, and there is no amount of computational power that can capture and aggregate the information in abstract terms. For Hayek and his followers, man is an irredeemably, constitutionally limited creature and politics must be done, and policy made, accordingly.

Together, these knowledge problems lead Hayek and his acolytes to favour market-solutions to the problems of distributing goods, where supply is coordinated with demand by individual decision-making and decentralised price mechanisms rather than by government diktat. In his Knowledge and Decisions (profoundly influenced, the acknowledgements explain, by Hayek’s original essay), Thomas Sowell gives a useful account of what this means in theory –

Both the friends and foes of economic decision-making processes refer to ‘the market’ as if it were an institution parallel with, and alternative to, the government as an institution. The government is indeed an institution, but ‘the market’ is nothing more than an option for each individual to choose among numerous existing institutions, or to fashion new arrangements suited to his own situation and taste.

The government establishes an army or a post office as the answer to a given problem. ‘The market’ is simply the freedom to choose among many existing or still-to-be-created possibilities. The need for housing can be met through ‘the market’ in a thousand different ways chosen by each person – anything from living in a commune to buying a house, renting rooms, moving in with relatives, living in quarters provided by an employer, etc. etc. The need for food can be met can be met by buying groceries, eating at a restaurant, growing a garden, or letting someone else provide meals in exchange for work, property, or sex. ‘The market’ is no particular set of institutions.12

Given that technocratic central planning depends on making impossible knowledge claims, a system that leaves people alone to exercise their local, tacit/practical knowledge in pursuing their needs, to associate and enter contracts at will, and that allows prices to provide them with a rough understanding of what others need/have, is preferable. In this way, the knowledge problem is taken to present a challenge to technocratic government and ‘the market’ is duly offered as a solution. Per Sowell, ‘the market’ does not refer to any particular set of institutions but rather to people’s – our – freedom from technocratic intervention – it is little more than the absence of technocracy.

Now, this line of reasoning is elegant, internally coherent, and would be more convincing if it were not wholly divorced from the realities of policy-making. The problem is that, in practice, technocrats can deploy the knowledge problem (and knowledge problem-style arguments) to make policy without it undermining their authority to set the terms of policy-debate or decide on the shape of its outcomes. In the next section, I will illustrate this using an example drawn from Annelise Riles’ ethnographic work at the Bank of Japan.

§ ‘Knowledge Problems’ at the Bank of Japan.

Very often, a central bank’s mandate includes overseeing commercial banks’ activities and ensuring their continued solvency. As a part of this, central banks act as commercial banks’ clearinghouse, transferring funds between them. If Bank A owes X amount to Bank B or decides to borrow Y amount from Bank C, the central bank moves the money by debiting/crediting their accounts as needed. There are multiple ways for a central bank to do this and up until January 2001, the Bank of Japan relied on a system called ‘Designated Time Net Settlement’ (DTNS).13 In her essay, Riles provides a helpful account of the system and its underlying rationale –

“[Commercial banks] accumulated obligations to one another throughout the day and then, at a designated time each day, calculated the balance of who owed what to whom. […] Planners [i.e., central bankers] reasoned that it made little sense for Bank A to raise funds to pay Bank B one billion yen at 10:00 am, for example, if Bank B needed to pay Bank A two billion yen in a separate transaction at 02:00 pm the same day. The central bankers therefore had laboriously worked out the details of a system by which banks extended each other credit throughout the day and settled all their transactions at once, at a designated time.”14

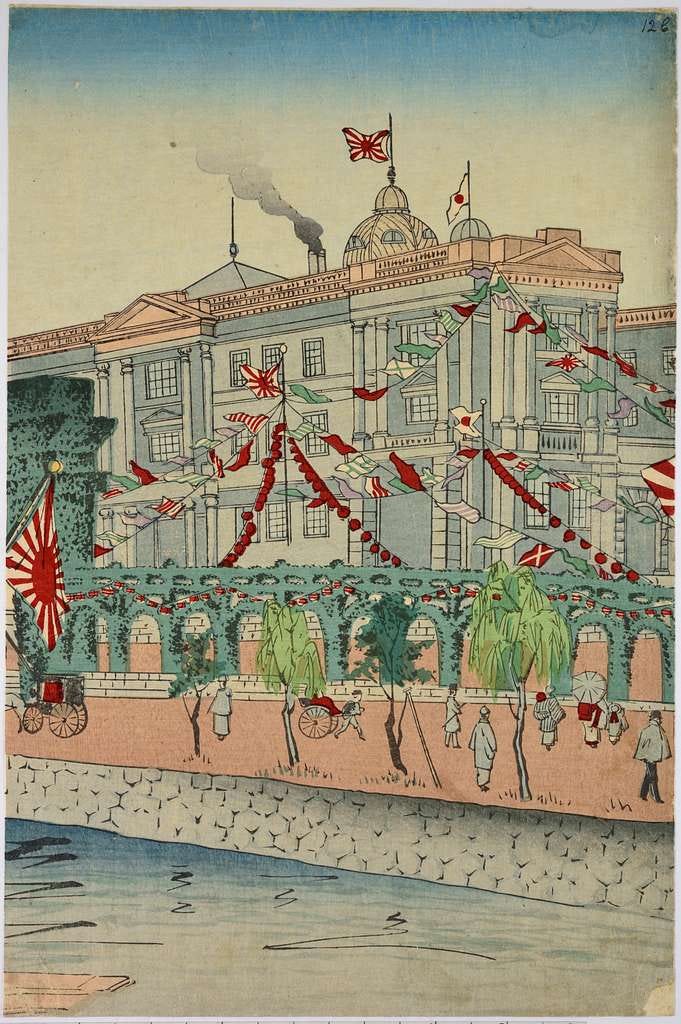

DTNS was an exercise in quasi-planning and imposed the central bankers’ judgement about when intra-bank payments were best settled, rather than just leaving the banks to work it out amongst themselves. This was in keeping with the broadly interventionist norms of Japanese policy-making, whose origins lie in the modernising reforms of the Meiji Restoration.15 As with most other nations, modernity inaugurated in Japan a number of programmes requiring extensive – and often granular – powers of intervention into citizens’ lives, including state welfare, public sanitation, and industrial policy. There was, however, also something distinctive about how the Meiji, and later Taisho, Showa, and Postwar technocrats exercised these powers in that, rather than deploying formal/legal obligation or violent coercion to achieve their ends, they relied on strategies of moral suasion, informal guidance, and the manipulation of social ties and obligations.16 Japan’s central bankers were little different. Like much of Japanese society, Japan’s banking sector was (is?) shaped by a dense matrix of overlapping ties of social obligation and of mutual accountability, reaching all the way up to the Ministry of Finance and the Bank of Japan.17 These ties, Riles’ interlocutors explained, were precisely what allowed them to intervene in DTNSesque ways –

Central bankers regularly “made use” of personal friendships to “collect information”, [she] was repeatedly told. Their task depended on – indeed, principally consisted in – gathering and dispersing information, on knowing the intimate details of what was happening within each institution, before it happened, and on coordinating a solution before problems mushroomed out of control […] Often, these bureaucrats defended their actions in terms of neoclassical economic theories of market knowledge in which, because the market immediately absorbs knowledge into price, knowledge that is publicly held is, by definition, already worthless. If they waited to address the market’s problems until everything had become publicly known and stock prices has plummeted, they would surely be blamed for failing to act quickly enough, they lamented.18

In this way, the BOJ’s central bankers/technocrats/planners and the DTNS system conformed to the account of technocracy given above. The former (like all Japanese technocrats) conceived of their target systems as inherently unstable and in need of intervention based on information that they gathered, distilled, and interpreted, and the latter represented one such intervention.

However, by the late 1990s (incidentally, around the time when Hayek’s ideas were beginning to percolate through the Japanese intelligentsia), this status quo was out-competed by a new conception that called DTNS into question.19 The public mood at the time was (by Japanese standards, at least) roundly anti-technocratic. Over the preceding decade, the unravelling of the ‘bad loans’ and the housing market’s ensuing collapse had revealed the perils of wanton intervention, and technocrats were under attack for systematically failing to let ‘the invisible hand of the market’ operate.20 The BOJ’s internal debates over DTNS were a microcosm of these broader shifts in the Japanese political cosmos.

These debates centred around the problem of ‘systemic risk’. Central bankers realised that demanding that banks settle their net obligations in one go, at a designated time at the end of the day, entailed what the Bank of International Settlements called a ‘systemic risk’ and defined as ‘the risk that the inability of one institution to meet its obligations when due will cause other institutions to be unable to meet their obligations when due.’21 For example, if Bank B was depending upon a payment from bank A at the end of the day to pay off its obligations to Bank C, Bank A’s defaulting could imperil all three members of the exchange. Crucially for our purposes, the BOJ bankers interpreted this risk in terms of the limits of their own knowledge – that is, they deployed knowledge problem-like arguments to make sense of the ‘systemic risk’ associated with DTNS.22 Following a global trend in the central banking community, they concluded that the DTNS system was predicated upon knowledge claims made impossible by the banking system’s computational complexity and a contextual uncertainty how financial law would be used to deal with a particular bank failure.

These concerns led the BOJ’s staff down a line of reasoning similar to that of Hayek and his adjacents. Construed as a failure of technocratic knowledge, DTNS’ systemic risk seemed to justify moving to an interbank payment system that no longer principally depended upon central bankers’ judgement about when transactions should be executed.23 So, again following a global trend, the staff moved towards using a new system known as ‘Real Time Gross Settlement’ (RTGS). Under its aegis, banks settled individual transactions, as they arose. If Bank A owed Bank B one billion yen at 10:00 am, then it was to pay Bank B one billion yen at 10:00 am, regardless that Bank B might in turn owe Bank A two billion later the same day. Exchange was to be spontaneously driven by banks’ local decision-making, rather than tied to centralised technocratic judgement.

This switch from DTNS to RTGS, from something plan-like to something market-esque, illustrates the knowledge problem’s failure to meaningfully challenge the technocratic exercise of power as I schematised it above. It shows how an argument ostensibly developed to challenge technocrats’ competence and legitimacy can be – and is – used by those same technocrats to frame and rationalise their policy debates and decisions (parts one and two of my schema, respectively). The BOJ staff’s theorising about the limits of their knowledge about interbank payments did not call into question their right to set the terms and shape the outcomes of debate over central bank policy. Indeed, that theorising was deployed by the BOJ technocrats to make policy, much as their counterparts in a Ministry of Finance or Department of Public Health might deploy macroeconomic or epidemiological theory to structure fiscal plans or design lockdowns. At most, we should follow Riles in observing that, contra Hayek and Sowell, knowledge problem-style arguments do not result in an absence of technocracy, but technocracy of a peculiar sort – one not predicated on positive claims about the nature of a system but on negative claims about the policy-maker’s limits.24 A technocracy that seeks its own effacement remains technocratic all the same.

This raises a potentially troubling question for would-be critics of technocracy, swayed by the knowledge problem’s critique of human cognition – what exactly is their, our, political project? How would we like to see political power exercised? The BOJ’s experience suggests that we should rethink our knee-jerk opposition to technocracy, or at least become more discerning critics of it. It is not technocracy tout court that the knowledge problem undermines, but technocracy predicated on impossible claims about complex, multidimensional systems. And it is, as a result, entirely possible to embrace its epistemic pessimism while calling for a more perfect technocracy (one composed of men versed in Hayek, of course). After all, if we are to be governed by experts, why not let them be, first and foremost, experts in their own ignorance?

Mitchel Y. Abolafia, Stewards of the Market: How the Federal Reserve Made Sense of the Financial Crisis (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2020), 6.

I say ‘roughly’ because these are, in practice, often very difficult to distinguish – see Mitchel Y. Abolafia, ‘Narrative Construction as Sensemaking: How a Central Bank Thinks’, Organization Studies 31, no. 3 (1 March 2010): 349–67, https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840609357380.

Abolafia ‘Narrative Construction as Sensemaking’; Abolafia, Stewards of the Market.

Mitchell Abolafia describes, for example, how monetary policy committees within central banks open their meetings by trying to establish the terms in which ‘The Economy’ is to be understood and discussed, usually by choosing within a repertoire of well-established macroeconomic indicators like CPI, PMI, the re-pricing of risk premiums, or whatever.

Annelise Riles, ‘Real Time: Unwinding Technocratic and Anthropological Knowledge’, Cornell Law Faculty Publications, 1 August 2004, 393, https://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/facpub/996.

F. A. Hayek, Individualism and Economic Order (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1996), chap. 4. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/I/bo26122439.html.

Don Lavoie, ‘The Market As A Procedure for Discovery and Conveyance of Inarticulatable Knowledge’, Comparative Economic Studies 28 (Spring 2001); Lynne Kiesling, ‘The Knowledge Problem’, in The Oxford Handbook of Austrian Economics, Oxford Handbooks in Economics (Oxford University Press, 2015), https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199811762.013.3.

In principle, many different sorts of central planning are possible (technocratic, plutocratic, democratic, etc.) but in this essay, I’m narrowly focussed on its technocratic variant. As such, every time I refer to ‘central planning’ or ‘planning’, I mean ‘technocratic central planning’.

Hayek, Individualism and Economic Order.

Kiesling, ‘The Knowledge Problem’.

And this will not improve with the advent of artificial ‘intelligence’ and machine ‘learning’! See Mark Pennington, ‘Hayek on Complexity, Uncertainty and Pandemic Response’, The Review of Austrian Economics 34, no. 2 (1 June 2021): 206, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11138-020-00522-9.

E.g., Marshall Sahlins, Culture and Practical Reason (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1978), https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/C/bo41988604.html; James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020); Hayek, Individualism and Economic Order; John Gray, Hayek on Liberty, 3rd ed. (Routledge, 1998); Lavoie, ‘The Market As A Procedure for Discovery and Conveyance of Inarticulatable Knowledge’; Hubert L. Dreyfus et al., eds., Skilful Coping: Essays on the Phenomenology of Everyday Perception and Action (Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 2016); Charles Taylor, Philosophical Arguments, Revised ed. edition (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1997); Michael Polanyi, The Tacit Dimension, Revised ed. edition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009).

But to be honest, if you’re interested in this question, you can really do no better than Hubert Dreyfus! His view is arguably the most radical of those cited, but it is also convincingly defended across a career’s worth of systematic, limpid, and ingenious books and essays.

Thomas Sowell, Knowledge And Decisions, Revised ed. edition (New York: Basic Books, 1996), 41. [Emphases in original]

Bank of Japan, ‘Introduction of the New RTGS System : 日本銀行 Bank of Japan’, Bank of Japan, accessed 5 September 2024, https://www.boj.or.jp/en/paym/bojnet/rtgs/set0101a.htm.

Riles, ‘Real Time’, 394.

Riles, 396; Sheldon Garon, Molding Japanese Minds: The State in Everyday Life, Revised ed. edition (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998).

John Owen Haley, Authority without Power: Law and the Japanese Paradox, Studies on Law and Social Control (New York, New York ; Oxford University Press, 1991); Garon, Molding Japanese Minds.

I have written about how this played out in the context of Japan’s COVID-19 response here 👉

Gillian Tett, Saving the Sun: A Wall Street Gamble to Rescue Japan from Its Trillion-Dollar Meltdown (New York, NY: Harperbusiness, 2003).

Riles, ‘Real Time’, 396.

Gilles Campagnolo, ‘Hayek au Japon : la réception d’une pensée néolibérale’, Revue de philosophie économique 17, no. 1 (7 December 2016): 171–208, https://doi.org/10.3917/rpec.171.0171.

Tett, Saving the Sun; Riles, ‘Real Time’, 395.

Bank for International Settlements, 1992. Delivery versus payment in securities settlement systems. Bank for International Settlements, Basle, Switzerland. https://www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/d06.pdf

Riles, ‘Real Time’, 395.

Riles, 396.

Riles, 397.

TYPO, I think, Mr. Max:

------------

This switch from DTNS to RTGS, from something plan-like to something market-esque, illustrates the knowledge problem’s failure to meaningfully the technocratic exercise of power as I schematised it above.

------------

Either a verb is missing after "to" -- or something else is the problem.

P.S. I found this piece interesting, but (as is your style/approach/personality) too understated/reticent. You might want to consider being more direct, forthright, bold to offer conclusions, remedies/alternatives, and/or your opinions/ideas. Perhaps--to round things out--you could do this by using a different, commonly-familiar, and/or simpler technocratic circumstance to illustrate (brief, practical application--way to look at/analyze--that is more tangible to average Joe and his real-life experience as a technocracy victim).