"Bioterrorism" as a Precondition of Lockdown-till-vaxx.

Senator Bill Cassidy's (accidental?) insight.

A couple of months ago, I attended the Pandemic Policy: Planning the Future, Assessing the Past conference at the University of Stanford. It was good fun, if somewhat limited in scope, and hosted a number of well-known speakers across four panel discussions.1 Amongst these speakers was Dr Monica Gandhi, an infectious disease physician at UC San Francisco and specialist in HIV/AIDS, who spoke on the first panel on ‘evidence-based decision making during a pandemic’. During her opening remarks, Dr Gandhi made a thought-provoking observation about the contrast between American public health’s response to COVID-19 and its response to HIV/AIDS—

[D]uring the pandemic is I was coming from an HIV doctor perspective because I'm a infectious disease doctor but do a lot of HIV. And so I looked back at the […HIV pandemic, at the beginning of which…] there was a very compassionate response from the public health community. There was a question of meeting people where they were, figuring out what they needed. And I'm not talking about the political community; I’m talking about infectious disease doctors, the public health Community, [for whom] the idea was that we couldn't keep people away from each other just because there's an infectious pathogen, that in this case was spread sex actually, and that [we should] use a harm reduction model and figure out what people needed and then, within that concept of what was needed, keep them safe.

(From timestamp 02:42 | Emphases mine, obvs)

This chimed with things that I have read elsewhere—Virgina Berridge, for example, speaks of a ‘liberal consensus’ amongst the UK’s HIV/AIDS public health scientists and policymakers—about public health’s general aversion to coercion and paternalism in WWII’s wake, and prompts a troubling question: ‘what changed in the forty years between AIDS and COVID-19 to make public health lose its commitment to liberalism and individual rights?’ What happened to put coercion and paternalism back on the menu?2

§ Gandhi’s explanation.

Gandhi’s own explanation of this reversal is vague (I grant that this may not have been the forum for a detailed retelling of recent public health history). She says—

…I think what happened at the beginning of HIV is that the president the time was conservative and so the public health Community, which usually leans left, was very opposed to ‘just say no’ and and sort of principles that were very harsh and did not in any way take into account human needs and the public health Community I think developed a very compassionate response to HIV […] I think what happened with COVID is that the the president at the time in the United States was conservative so the public health Community went oppositional. But the problem was that that was really political in the sense that things like school openings, things like people's needs were not taken into account because everything was sort of in reaction as opposed to a very clear scientific response.

(From timestamp 04:04 | Emphases mine, double obvs)

As I say, I don’t wholly understand what she is saying here. Clearly, she thinks that partisanship played an important role in shaping the left-leaning public health community’s response to HIV/coof and that they repudiated/embraced coercion in reaction to a right wing incumbent—in this case, Ronald Reagan and Donald Trump. However, she is unclear about which aspects of the Reagan and Trump incumbencies she takes public health to have been reacting to. Was it their specific responses to HIV and COVID or the overall tone or vibe of their policy? For my part, I think the latter (why else would she mention Nancy Reagan’s Just Say No campaign3 against drug-use?) but it matters little because her ‘partisan politics’ explanation of public health’s reversal is ultimately lacking.

I don’t want to suggest that there is nothing to this explanation. Public health, like any other community embedded in policy-making circles and civil society, is responsive to perverse partisan dynamics and there is plenty of evidence that said pressures played a role in our responses to COVID.4 However, it also does not do justice to the complex interplay of sociological, cultural, ideological, and techno-material factors that shape an institution like public health’s evolution—and, perhaps most egregiously for a public healthist like Dr Gandhi, robs public health of its agency and substance.

If we see public health as always essentially being in reaction to its political opponents, then we obscure the role played by its internal ideas, decision-making processes, and histories. In fact, taken to its caricatural extreme, the good doctor seems to conceive of public health in the way that Beauvoir claimed patriarchy conceives of women—as another entity’s negative image, or ‘other’, lacking its own essential characteristics. To anyone with even a passing understand of what public health is and does, this is obviously not satisfying.

§ Bioterrorism as a precondition of lockdown-till-vaccine.

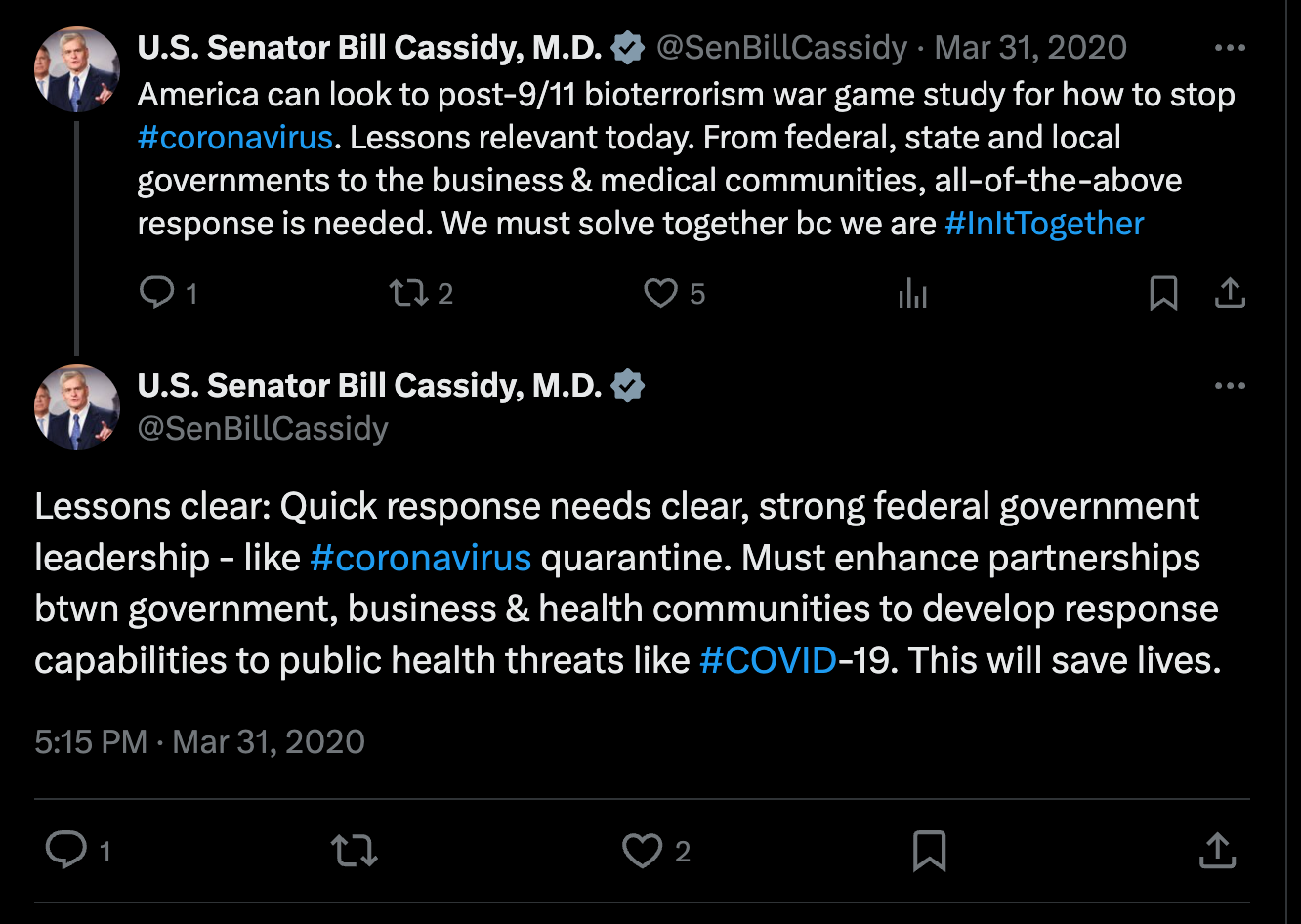

So what is a better explanation of the reversal (i.e., one that pays close attention to public health’s own shifting priorities and ideas)? Well, the answer is complex and multidimensional but I recently stumbled across the following tweet by US Senator Bill Cassidy that points to something critical—the role played by (the phantasm of) bioterrorism.5

As you can see, Cassidy—a hepatologist, Senator, and member of the influential Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP) committee—suggested relatively early in the COVID-19 pandemic that policymakers draw on exercises run by the Bush administration in the wake of SARS-1, 9/11, and the anthrax letters, simulating the US military’s response to bioterror attacks (notably Dark Winter and Atlantic Storm).6 While I haven’t yet found much evidence that American policymakers actually consulted these exercises’ findings in designing and implementing their policy response (I admit it, dear reader: I am yet to muster the inner strength to read Deborah Birx and Anthony Fauci’s books…), this tweet is interesting for what it reveals about the mindset or paradigm dominating public health in 2020, that conceives of infectious disease outbreaks as analogous to terror attacks and, dating back to the early 2000s, was instrumental in making the lockdown-till-vaccine thinkable and feasible.

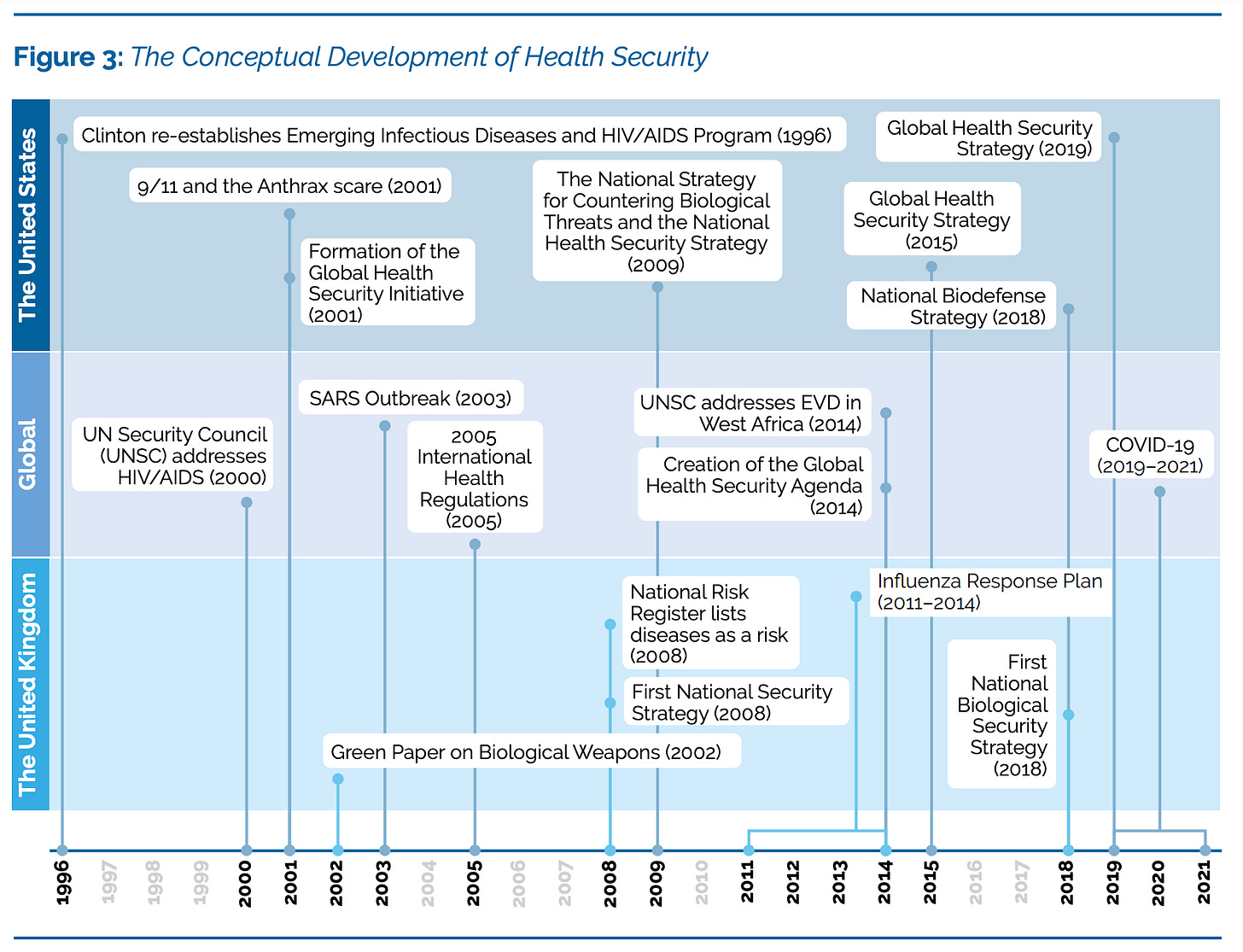

I don’t yet know how to refer to this paradigm. In a 2021 report on Health Security, Nina Gerami and colleagues propose the term ‘health security’ (as good a name as any), explaining that it is,

…based on the premise that infectious disease could jeopardise the security of the national-state and the integrity of territorial borders, implying that (global) health security requires a state-centric response. The state-centric nature of this approach has entailed a particular narrative of health security centred around prevention and responses to biological threats, whether naturally occurring, deliberate, or accidental […] This framing has placed public health, infectious disease, and bioterrorism under the umbrella of health security which has become a vague, catch-all notion used to describe nearly any public health emergency.7

[again, emphasis mine.]

Under the ‘health security’ paradigm, outbreaks of infectious disease are effectively thought of as external invaders of some sort, threatening the health and functioning of the national body politic. On these terms, infectious disease is neither an act of God nor a hard fact of being human but an aberration and a threat to the social fabric. And, as Philipp Sarasin schematised, this nightmare of disease-as-social-contamination or a festival of disorder invites in return the dream of a society in which it has been eliminated (or, at least, controlled) and order duly restored.8 Health security, in other words, lays the ideological foundation for sweeping coercion and paternalism.

This dynamic—as Cassidy’s tweet implies—can be clearly observed in the evolution of post-9/11 and -anthrax policy making and disaster planning. Let’s briefly look at how.

§ Health securitisation after anthrax

[A lot of this section is adapted from my MPhil thesis on the UK’s decision-making during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Hopefully, a modified version of it will soon be available as a working paper so watch this space! 👍]

Arguably, health security’s roots arguably stretch back to the Koch school’s early conceptualisation of pathogenic microorganisms as ‘foreign invaders’, or even further back to the very foundation of national public health systems. However, it was only with (inter alia) the crystallisation of elite fears about terrifying diseases as the consequence of hostile actors’ nefarious actions (i.e., fears about bioterrorism) that it percolated into national security policy and, eventually, pandemic planning.9 From the early 1990s, worries about the risks of burgeoning migratory flows, disgruntled ex-Soviet scientists, and hostile foreign powers (alongside airport thrillers like The Cobra Event, which Bill Clinton read and was alarmed by…) coalesced into an entirely hypothetical anxiety about ‘bioterror’ which, Sarasin explains,

…turns out to be the quintessential expression of fear of “infection” in the age of globalisation. Whereas illegal migrant workers represent the average risk of infection, which every tourist is also exposed to, “bioterror” connotes the—apparently objective—maximal threat of pathogenic agents, against which there is no protection.10

In this sense, 2001’s anthrax letters were two attacks in one.11 The first was biological and only modestly impactful, killing five and ostensibly infecting seventeen others. The second was symbolic and, by making the national security elite’s hypothetical fear real, enormously consequential, triggering a spate of policy-making processes that closely followed Sarasin’s schema.

Following 9/11-inflected-by-anthrax, the American state launched a reappraisal of its biosecurity response capacities.12 Essential medical stocks were audited, emergency communication systems checked, and the Centre for Disease Control (CDC) asked that state governments consider extending the emergency powers at their disposal in the event of a bioterror attack. To help them with this, CDC published The Model State Emergency Health Powers Act (2001), which provided states with a model of the sorts of powers that it (the CDC) hoped they would accord themselves.13 And, nestled amongst provisions for commandeering medical facilities or surveilling doctors and nurses, were a number of recommendations about the mass-quarantining of asymptomatic individuals—including, significantly, the suggestion that said individual’s failure to comply be punishable by law.14

Unsurprisingly (or so it was, once upon a time), the Model Act faced a great deal of opposition on all of the American political spectrum (from right-leaning libertarians to left-wing liberal progressives) on the basis that it violated the understanding of human flourishing ratified in the American constitution, whose fourth amendment protects a citizen’s right to privacy, free of unwarranted intrusions by the state.15 In-spite of such bipartisan resistance, however, a Public Health Security and Bioterrorism Preparedness and Response Act (2002) was eventually passed, extending the federal government’s scope of legitimate intervention to include asymptomatic people.

As Sarasin saw, the phantasm of bioterror begat a call for the power to mobilise society at large—a call that very quickly bled into infectious disease planning more broadly. Over the summer ‘05, President GW Bush read John Barry’s authoritative study of 1918’s Spanish flu, The Great Influenza, and, still reeling from 9/11, anthrax, hurricane Katrina, and SARS-1, returned from his holiday with a fresh interest in the threat posed by disastrous outbreaks of infectious diseases. With this in mind, he organised an internal overhaul and two doctors, an oncologist named Richard Hatchett (now CEO of CEPI) and an emergency-room physician called Carter Mecher (still pottering about somewhere), were put in charge of designing a strategy fit to face the 21st century’s terrors.

Both men (although, Hatchett in particular) were fascinated by the computer modelling of disease spread and by the insights into the possible methods of control that it promised. Drawing on modelling by Robert Glass, a scientist at the secretive Sandia National Laboratories, as well as their own original research into the partial shutdown of cities during the Spanish influenza, Hatchett and Mecher concluded that large-scale quarantines could be used to control, and even suppress, the spread of disease. Accordingly, through 2006 and 2007, they produced a pandemic influenza plan that referred to a strategy called ‘targeted layered containment’, which involves the progressive layering of non-pharmaceutical interventions like telework, school closures, social distancing, and the cancellation of mass gatherings, culminating in situation that resembles a large-scale quarantine or lockdown.

With this, the (bio)securitisation of public health was underway. The spread of infectious disease and deliberate acts of bioterror were collapsed into a single category—threats to national security—to be thought of and dealt with in similar ways. Conceiving of disease in this way, as an aberrant, alien festival of disorder, led certain public healthists to have policy dreams of mass-quarantine, of totalising discipline and control. Coercion and paternalism began to make their way back onto public health’s roster of interventions—and a little over a decade later, nearly half of the world’s population found themselves placed in ostensibly unprecedented lockdowns.16

This, in my humble opinion, is the start of a much more satisfying answer than Monica Gandhi’s.

For more on ‘lockdown-till-vaccine’, see 👇

Was the COVID Vaccine a "Success"?

“…when social processes are described in terms of their hoped-for results, this obscures the more fundamental question as to just what they actually do - and circumvents questions as to whether doing such things is likely to lead to the results expected or proclaimed.”

Virginia Berridge, AIDS in the UK: The Making of a Policy, 1981-1994 (Oxford: University Press, 2002); Toby Green and David Bell, ‘The World Health Organisation and COVID-19: Re-Establishing Colonialism in Public Health’, PANDATA: Data & Analytics, June 2021; Patrick Zylberman, ‘Civilising the State: Borders, Weak States and International Health in Modern Europe.’, in Medicine At The Border: Disease, Globalization and Security, 1850 to the Present, ed. A. Bashford, 2006th edition (Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire England ; New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006).

I also recognise that the full story is actually more complicated than this and that even in its most liberal, public health continued to endorse forms of coercion like the mandatory isolation of early AIDS patients, the forced sequestration and drugging of the mentally ill, and vaccine mandates in schools. I am also not saying that coercion is everywhere and always bad (some mentally ill people do need to be forcibly detained and treated). For the purposes of this blogpost, however, I am painting in broad historical strokes and largely focussing on forms of coercion (mandatory mass-quarantine, mask-wearing, and -vaccination) that I do, by and large, consider unacceptable.

Dan Zak et al., ‘On Drugs, Nancy Reagan Just Said No. On AIDS, She Said Nothing.’, Washington Post, 12 March 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/on-drugs-nancy-reagan-just-said-no-on-aids-she-said-nothing/2016/03/11/3f9d59e8-e483-11e5-a6f3-21ccdbc5f74e_story.html.

Toby Green, The Covid Consensus: The New Politics of Global Inequality (London: C Hurst & Co Publishers Ltd, 2021).

Philipp Sarasin, Anthrax – Bioterror as Fact and Fantasy, 1st edition (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2006).

Patrick Zylberman, Tempêtes microbiennes: Essai sur la politique de sécurité sanitaire dans le monde transatlantique (Paris: GALLIMARD, 2013), chap. 3.

Nima Gerami, Amanda Moodie, and Federica D’Alessandra, ‘Rethinking Health Security after COVID-19’, 8 November 2021, http://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/publications/rethinking-health-security-after-covid-19.

Philipp Sarasin, Anthrax – Bioterror as Fact and Fantasy, 1st edition (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2006). p.230

Sarasin 2006, p.176 and Zylberman 2006. (Per what I said in Endnote 2, coercion and paternalism have never been wholly alien to public health…)

Sarasin 2006, p.222

Sarasin 2006, p.136—There is an important argument to be made here that the ‘Wuhan coronavirus lab leak’ narrative has had a very similar effect!

Zylberman 2013, p.401

Lawrence Gostin, ‘The Model State Emergency Health Powers Act’, 2001, https://publichealth.jhu.edu/sites/default/files/2023-06/msehpa.pdf.

Gostin 2001, p.27

Zylberman 2013, p.402—This puts me in mind of something that Mike Casey often says: the War on Terror, like the War on COVID, was a radicalisation of the centre, not the fringes. Read his excellent piece on COVID-19 👉 here 👈.

The story of what happened in the interim is for another day. My thesis touches on it a little… again, watch this space!

Howdy, Mr. Max, Since you haven't posted about this new Substack at your Xwitter, you made me log in here to tell you this — and show you this…

Cassidy is typical Uniparty Right (calls himself "Republican"). He's awful (I say this from the Right and as an American). He's also the typical U.S. Senator who fancies himself as a big deal re biodefense (biodefence) and national security™. Btw, national security vis-a-vis scamdemics and CBRN threats/incidents also includes (going back to GW Bush the Catastrophizer) "critical infrastructure" and "key resources." It's that construct that gave us essential and nonessential. Cassidy's "conservative" rating is reliably an F+ or a D-. I am NOT a fan of the man.

What I want to show you is this document:

https://centerforhealthsecurity.org/sites/default/files/2023-10/cassidy-cdc-rfifinal.pdf

It represents and encapsulates "health security" meets Public Health (in form of the USA's primary PH agency, the CDC). The document at every turn is a puzzle piece — adding up to many puzzle pieces. For your thesis (or theses). Johns Hopkins (which is treated like a Branch of the Federal Govt by the actual Constitutional Branches of the Fed Govt) tells us what they want the ever-expanding, out-of-control "public health" apparatus to be. It's a nightmare. You can figure out the rest as you wade thru the RFI and see how it fits in with your work.

I agree that your explanations-in-progress are more promising than Ms. Ghandi's.

Carry on/all the best, @mdmstakeholder😎