A version of this essay was very kindly published by Café Americain. You can read it 👉 here 👈

On May 23, the fourth season of Clarkson’s Farm was released on Amazon Prime. Set to continue the story told across its three predecessors, the series depicts the often hapless efforts of Jeremy Clarkson, the British TV presenter turned self-made farmer, to farm his 1,000-acre estate and to run it as a profitable business (an ambition surely helped by Amazon’s yawning budget). Having enjoyed the show from its first season, I had been anticipating this release with some eagerness. Clarkson, a motoring journalist best known for presenting brash and blokeish shows like Top Gear and The Grand Tour, makes for a funny, affable, and surprisingly humane guide to his many exploits and misadventures, while the panoramic shots of his Cotswold neighbourhood provide a welcome reminder of just how beautiful England is, or can be. The show is also an unlikely, and yet thought-provoking, vignette of rural politics and policymaking.

For example, Season 1’s episode “Wilding” centres on Clarkson’s attempts to “wild” (or “rewild”) portions of his land. It opens with an amusing speech by Clarkson, delivered from behind the wheel of his Range Rover, worrying aloud about the UK’s flagging levels of biodiversity: “If I’d driven along here [a country lane] at this time of the year [Spring] when I first started driving thirty or forty years ago, after about five miles I wouldn’t have been able to see where I was going. My windscreen would have been an opaque smorgasbord of dead insects. But look at it now … [gestures theatrically] there’s nothing! You get more flies on the front of a submarine!” Agricultural development and expansion in the post-War period, he continues, now standing before a heavenly patchwork of fields and trees, decimated insect habitats: “Since the war, Britain has lost 140,000 miles of hedgerows; it’s lost 40% of its ancient woodlands; and it’s lost 97% of its wildflower meadows” (I have not, gentle reader, fact-checked these claims). The solution, Clarkson concludes, is a strategy called “wilding”, which entails leaving “chunks of the farm completely alone. I’m going to put Mother Nature in the driving seat”. It was this metaphor that piqued my interest: Clarkson, like most of his fellow wilders—i.e., other landowners turning portions, even the entirety, of their farmland over to Mother Nature’s designs—sees himself as relinquishing his control of the land in some way. For them, “wilding” is a withdrawal, a rolling back of the agriculture that has led to biodiversity decline, and a giving of space to the multifarious, complex processes of organic growth and diversification (i.e., “Mother Nature”) that might allow biodiversity to tick up once more.

Yet this self-conception, though common amongst wilders, is an egregious misunderstanding of what “wilding” is, and it is entirely belied by the rest of the Clarkson’s Farm episode in question. To see why, let’s more carefully consider the type of control—what we might call “agricultural control”—that “wilders” take themselves to be relinquishing. Broadly speaking, agricultural control has at least two dimensions:

Identifying and delimiting a domain of intervention (often by physically erecting a boundary hedge or fence to create a farm or a field within it)

Designing and then imposing a planned order within that domain (for instance by planting with neat rows of a single crop, or by clearing the land of brambles to make way for a herd of cows to raise for milk or meat)

All three seasons of Clarkson’s Farm are littered with examples of this form of control. Standing before a map in his office, Clarkson designates certain patches of land as being for wheat, rapeseed, barley, sheep, cows, pigs, and even goats, and then farms them accordingly. The “wilding” strategy is supposed to be a suspension, even a reversal, of that, but closer examination of how it fits with agricultural control’s two dimensions suggests that this is not what happens in practice.

Let’s start with (1). Wilders like Clarkson do not actually relinquish their control of their land insofar as “wilding” involves them identifying a patch of land to be rewilded. I am not making a point about the evils of private landownership here (not least because states or collectives could run wilding projects and because private landownership can have salubrious, pro-social consequences), but simply noting that this aspect of agricultural control is constitutive of what “wilding” is. “Wilding” is impossible without someone there to delimit a domain of intervention, that is without an aspect of precisely the exercise of control that it promises to relinquish. Mother Nature, keen motorist though she may be, needs to be put in the driver’s seat by precisely the one (Clarkson, in this case) trumpeting his relinquishing of control.

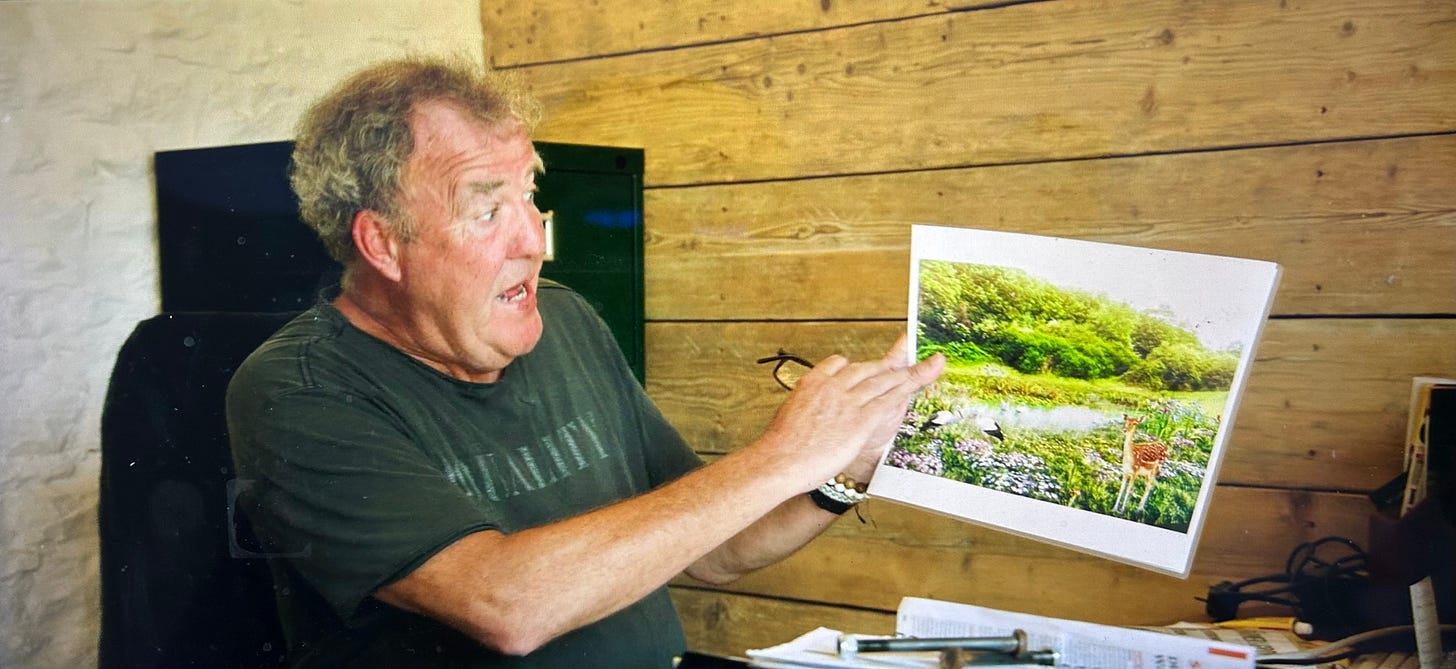

This brings us to (2), where things get a little more complex. While it is not possible to imagine “wilding” without a wilder to set aside a packet of land for that purpose, it is possible to imagine said wilder then truly withdrawing from his domain. This would mean that the wilder accepts that que sera, sera, even if that means nothing growing, things dying, or an invasive species outcompeting more delicate or prettier natives. Each of these events is, after all, in Mother Nature’s repertoire. The problem, of course, is that few if any wilders are actually willing to embrace these outcomes. Most wilders “wild” their land with some goal in mind, such as improving its biodiversity, aesthetics, or, as one can’t help noticing in the FT Weekend’s coverage of wilders, their social status. To his credit, Clarkson seems to be primarily motivated by the first two, illustrating his hoped-for result with a bucolic image complete with thick green foliage, a pair of storks, and a foal standing in a limpid pond (see below). Accordingly, throughout the episode Clarkson is shown intervening in all sorts of ways to help Mother Nature boost biodiversity and beautify the “wild” patch of his farm: he fells trees to maximise the sunlight reaching the forest floor and encourage wildflower growth, erects boxes for owls to nest and breed in, and dams a river to create a wetland in the hope of attracting bugs, kingfishers, and, less seriously, otters.

If Clarkson the wilder can be said to be relinquishing control here, it is only in a very qualified sense: he recognises that boosting biodiversity depends on a mess of low-level organic processes that he cannot hope to micromanage, but he nonetheless retains control by hewing to that overall goal and intervening to nudge those processes in the right direction. In this way, while the wilder’s exercise of control is not identical to the agriculturalist’s—insofar as he does not seek to impose a wholly planned order on his land—but neither is it a clean break from or reversal of the latter. The wilder does not, properly speaking, relinquish his agricultural control of his land, but realises that to achieve his goals he must rely on processes that are too varied and complex to wholly specify or plan. So, within his project’s parameters, he must allow for more self-government that the agriculturalist (who, pending technology that allows us to control the shape of every root and shoot, must already allow for some). “Wilding” is post-agricultural rather than non- or pre-agricultural: it does not abandon the basic structure of agricultural control, but does set aside its ambition to impose a totalising order within a particular domain.

“Wilding” is a quasi-paradoxical form of intervention, one trumpeting the intervener’s desire for self-effacement and is, in this way, analogous to programs of deregulation, “liberalisation”, and free market advocacy. Like “wilding”, such programs promise a relinquishing of state or bureaucratic control over a particular domain of intervention, but in practice mean something rather more complicated. Much of what is sold as deregulation or “liberalisation” actually involves bureaucrats reckoning with their inability to improve on complex, entangled processes within their domain of intervention and so trying to find ways of putting those processes to work for them. But like Clarkson, like the wilders, they do not thereby actually break with already existing structures of bureaucratic control.

Annelise Riles, a legal anthropologist, provides a neat example of this quasi-paradox in her work on Japanese central bankers. Amongst a central bank’s many jobs is to act as a clearinghouse for interbank loans and payments, which means facilitating the transfer of funds between private banks. The original transfer system, says Riles, was seen by its inventors as “a small technocratic triumph, an example of the contributions of planning to the smooth functioning of the market”. Central bankers argued that it made little sense for a bank to receive two billion yen from another bank in the morning if it was going to owe that same bank three billion yen in the afternoon, and that it thus made more sense for all the debts to be summed up and settled in one go at a time designated by the central bankers. This system was called, aptly enough, the Designated Time Net Settlement System (DNTS), and was structurally similar to the agricultural exercise described above: like the agriculturalist, the central banker presided over a domain of intervention (interbank payments) within which he imposed a totally planned order (obliging banks to settle their debts in one go, at a particular time).

Unfortunately, much as agriculturalists learned that their post-War activities had led to spiralling insect numbers, the bankers quickly realised that DNTS had an unexpected downside: if one bank defaulted on its payments at the designated time, this could lead to another bank defaulting on its payments, which could lead to another bank defaulting, and so on. This systemic risk, they concluded, was a product of the central bankers’ inability to exhaustively grasp and predict the complex relations that existed between the banks. Their response to this was to consider a new system called Real Time Gross Settlement (RGS) which proposed to leave payments to the banks’ discretion and to allow them to be settled in real time. And, again much like “wilding”, this change was sometimes (albeit not always) framed as an exercise in deregulation or the withdrawal of bureaucratic control over a particular domain: ‘‘Sometimes”, one of these bankers told Riles, “[market participants] say these issues should not be fixed as a market practice but through guidelines [i.e., planning] from the Bank of Japan, but we refuse. We say, we’re going to prepare a very flat table. And what kinds of plates and saucers you put on it is your own work’.”

As above, however, it is not clear that we should accept this self-description at face-value, and for much the same reasons. Like the wilders, Riles’ bankers did not give up on their capacity to set an overarching goal (clearing interbank payments in a timely and efficient manner), and would certainly not have accepted a situation in which the market participants’ “own work” failed to meet it. Instead, they found a way of achieving their goal that no longer relied on an impossible or precarious top-down ordering of their domain. Riles explains:

“What most clearly defined Real Time as an endpoint to technocratic knowledge was what would happen to social relations under the new system … [The central banker] excitedly described how Real Time would encourage ‘self-responsibility’ among market participants by requiring each to post collateral for the full value of his transactions in advance. [He] reflected in vivid detail to me about how, under Designated Time, bankers could just sit in their offices smoking away until the time of settlement each day. Under the new system, however, every second would count, and bankers would be forced to become far more alert, efficient, and nimble in their thinking. The initial chaos of Real Time, [he] argued, would eventually give way to a deeper level of order guided by ‘market practice’. The difference would be that this new order would emerge on its own, from the aggregation of the actions of individuals, rather than as an artefact of his and others’ planning”.

This remaking of social relations is (roughly) analogous to Clarkson’s efforts foster wildflower growth and attract otters, and like those interventions it belies any claim of relinquished control. The bankers, like Clarkson and the “wilders”, realised that their efforts depended on processes complex enough to defy planning, and so found ways of instrumentalising them (the processes). In doing so, they neither relinquished their capacity to carve out domains of intervention, nor their control over a domain’s overarching purpose, nor even the manner of achieving it. All they did was abandon the project of imposing a planned order within that domain. (Of course, this analogy can only go so far: there is an important, and interesting, difference between what Clarkson does in trimming foliage and what the bankers did in modifying the market participants’ reflexive self-understandings.)

Deregulation, like “wilding”, or “rewilding”, like deregulation, makes a paradoxical (even straightforwardly mendacious) promise to relinquish control of a domain while continuing to determine its shape and contents. Both deregulation and wilding are interventions (of a new kind, perhaps, but interventions nonetheless) masquerading as non-interventions, and so should be understood on the same terms: as historical evolutions in, rather than paradigmatic breaks from, an existing structure of intervention and control.

And on that bombshell…