Stuck in the long shadow of Hobbes’ Leviathan, Westerners have tended to make two assumptions about the exercise of political power:

That the State is, ultimately, the source of socio-legal order, and

That it enforces this order through a (thinly veiled) threat of coercive violence.

On these terms, a man does what the State asks because, whether he agrees with it or not, because he ultimately fears the State’s retribution. This folk-understanding of power lay fallow in many of the justificatory tales that erstwhile liberal democracies spun about the COVID-19 lockdowns and mandates imposed across the West. People, it was said, had to be compelled (i.e. mandated) to perform certain behaviours (like social distancing, masking, or getting vaxxed) because they could not be trusted to do the ‘right thing’ without the threat of violence1.

These narratives, however, are complicated by Japan’s response to the spread of the coronavirus. Unlike a great many of its counterparts, the Japanese state never resorted to a draconian lockdown-and-mandate approach. Instead, officials relied on ubiquitous public health messaging and unenforced ‘requests’ (gyōsei) for voluntary behaviour change, amongst which the most famous was their appeal for jishuku (Wright 2021; Borovoy 2022).

Roughly translated as ‘self-restraint’, jishuku refers to a well-established norm in Japanese statecraft of asking (but, again, not ordering) ordinary citizens to sacrifice their personal projects and interests to the common good – in this case, to suppressing the spread of COVID-19. It was first coined and invoked by the Japanese state at the height of WWII’s war effort, when the collective most depended on personal sacrifice, and then properly crystallised as a socio-political norm with the death of Emperor Hirohito in the late 1980s (Wright 2021, p464; Abe 2016, pp.243-247)2. When it was announced that the Emperor had finally succumbed to the duodenal cancer that afflicted him, a jishuku mūdo (‘mood of self-restraint’) was requested of the nation and

Without any formal mandates or legal regulations, sound, gestures of festivity, and performance in public spaces were discouraged. People remained indoors, glued to the TV. Stores stopped playing recorded music and sales pitches from the speakers. The streets were unusually quiet. Many sounds disappeared from public space, from the bass drums of the cheerleading team in the university league baseball game, to right-wing sound trucks, Christmas jingle bells and, of course, chindon-ya—the epitome of commercialism, festivity, and sound and performance in public space.(Abe 2016, p.245)

After that, jishuku was successfully used by the Japanese state in asking businesses to boycott Apartheidt South Africa; people to stop visiting the DPRK; and in the wake of the 3/11 disaster (the earthquake, tsunami, and Fukushima nuclear melt-down in 2011) (Wright 2021, p.462-466; Borovoy 2022, pp.15-22; Abe 2016, p.246). As a result, when SARS-CoV-2 began to spread in early 2020 and PM Shinzo Abe made his first request for jishuku, it was a well-established, even official, norm of Japanese policy – gaishutsu jishuku yōsei (‘a request for self-restraint in not going outside’) was mentioned in the 2013 Act on Special Measures against Novel Influenza and in the government’s key ‘Basic Policies for Novel Coronavirus Disease Control’ document (Wright 2021, p.455)3. However, whereas in 1989 the exercise of jishuku meant appearing sombre and not making too much noise, in 2020 it meant avoiding the ‘3 Cs’ (sanmitsu): closed spaces, crowded spaces, and close interpersonal interactions, as well as diligent face-masking and, when it became possible, getting vaxxed. As such, jishuku is not really a request for specific behaviours, but rather for a certain pro-sociality or compliance of attitude and disposition.

And, by its own standards, it seems to have been pretty successful! In the early months of 2020, Japan reported low COVID-19 case numbers and deaths, and though people continued grocery shopping and schools only closed for a few weeks in April 2020, people spent much less of their time commuting to or at work, and more of it at home (OurWorldInData 2020). Face-masks were also compliantly worn – so much so that they had to be actively discouraged during a heat-wave in 2022 and even now, months after the official advice was repealed, they continue to be very widely worn (Borovoy 2022, p.3; NHK 2022; NikkeiAsia 2023). And finally, despite initial fears about hesitancy, vaxx-uptake was high across most age groups and even exceeded some countries that took a coercive approach.

As I say, prima facie this could seem perplexing to Westerners. Contra our folk-understanding of power, here is a State that successfully incited collective (and, eschewing coyness, personally harmful) voluntary behaviour change through ‘requests’ alone, without resorting to the threat of violence encoded by mandates.

How is this to be explained?

§ Explaining Jishuku - Ideology versus Reality.

When asked to explain this success, officials often did so in terms of a distinctively Japanese ‘character’ or good manners. The late Prime Minister Shinzo Abe extolled the successes of ‘the Japanese model’ in managing the pandemic “[i]n a characteristically Japanese way” (Wright 2021, p.457; Borovoy 2022, p.14) and, echoing his boss’ sentiment, Deputy Prime Minister Taro Aso famously claimed that the Japanese possess a higher level of mindo (roughly, ‘social standards’) than other countries (Wright 2021, p.457), reflecting that:

I have received phone calls (from overseas) asking: “Do you have a drug that only you guys have?” My answer is the level of cultural standards is different, and they fall silent. The United States imposed fines on people who broke lockdown rules, and France did so too. But we didn’t have to do such a thing, and we made it only by requesting that people suspend non-essential businesses and stay at home. We should be very proud of this. (Taro Aso quoted in Ijima 2021)

These laudatory, culture-centric explanations were also widely disseminated in the West by a number of prestigious, high-circulation outlets (e.g. Japan Times; New York Times) that, like Abe and Aso, all emphasised a distinctive public-spiritedness or conscientiousness in the Japanese character that made its response possible. And, to their credit, they offered some nuance to our crude Hobbesianism by allowing that some States preside over populations who, for ‘cultural’ reasons, do not need it to enforce its edicts through coercion or the threat of violence. In other words, the docile and mature Japanese did not need the same domestication as boorish and unruly Westerners, and could be trusted to spontaneously, frictionlessly act in the interest of the common good without the use of mandates4.

Whatever their virtues however, these explanations also suffer from the vice of being mostly wrong in a way that obscures the less-flattering aspects of Japan’s COVID response that its political élites may prefer to see ignored.

Examining the situation more closely, it is clear that compliance with COVID gyōsei resulted from more coercion than these Abe-Aso-style explanations allow. People and businesses deemed to not be conforming to the state’s requests were subjected to extensive harassment campaigns by members of their community (Wright 2021, p.466 and Borovoy 2022, p.16). Shops and salons that chose to remain open were vandalised with signs telling them to go broke and die; cars with number-plates from other prefectures were egged; and, eventually, people grew terrified of others finding out that they had tested positive for COVID-19, for fear that this be taken as evidence of non-compliance. Amy Borovoy provides a number of grisly testimonials of this moralisation of coronavirus infection, including the following one:

…a woman described how she had been unable to tell her relatives of the death of her mother after her mother’s hospitalization. Her mother was taken to the hospital in an ambulance and her condition worsened quickly. She was never allowed to see the body before cremation or to visit the cremation site. Although her mother’s remains were now at her home, she hesitated to tell the neighbours and worried that they might smell the incense burning in the house when they came to collect monthly fees for the neighbourhood association. She complained that Covid-19 infection and even death is accompanied by moral judgement: ‘Those who are infected are looked down upon’ (shita ni mite iru), and those who avoid infection are regarded as virtuous (erai). (Borovoy 2022, p.18)

There were also reports of healthcare workers being assaulted and stones being thrown at COVID patients’ homes. Self-policing of this sort was so wide-spread that it was even named, jishuku keisatsu (‘self-restraint police’), and was declared the Japanese word of the year in 2020. Contra Abe-Aso then, the Japanese COVID response was not merely the product of “higher levels of mindo”, but also of vicious, extensive coercion. But contra sub-Hobbes, the people rather than the State were its source.

Importantly, this is not to say that the Japanese state had nothing to do with the jishuku keisatsu’s activities. On the contrary, exploiting a popular willingness to punish non-compliance was central to its response. Numerous state institutions, including the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare (MHLW), curated regularly updated lists of businesses and people that violated the state’s various quarantine and public health requests (Borovoy 2022, p.17; Wright 2021, p.467). And, alongside gaishutsu jishuku yōsei, the use of public naming-and-shaming had been explicitly written into the aforementioned Act on Special Measures against Novel Influenza etc. of 2013 (Wright 2021, p. 467).

Abe-Aso explanations do not fail entirely. As I will outline below, there are significant socio-cultural differences between the Japanese and Westerners that explain some of the differences between request- and mandate-based responses to COVID, and emergencies more widely. However, these do not account for the Japanese state’s explicit inclusion of jishuku and self-policing in its official policy, and its subsequent instrumentalization of them. Instead, I would suggest, this speaks to an exercise of political power that was not acknowledged by Abe and Aso (possibly deliberately) and is not conceived of by our mandate-happy cod-Hobbesians. It is neither quite top-down (like a mandate) nor bottom-up (like Abe’s “characteristically Japanese way”), but something that blurs the line between the two. Very clumsily, it could be described as ‘top-down by-way-of bottom-up’ and entails the State knowingly instrumentalising social norms to pursue political ends – hence resulting in what above I called a ‘socio-political’ norm.

§ The Socio-Historical Pre-conditions of Jishuku.

By definition, any socio-political norm has two aspects: (1) a people, shaped by various socio-cultural norms and customs, and (2) a State, ready and able to use those norms to achieve policy-ends. In jishuku’s case, the norm in question is a widely-shared ethos of outward conformity with authority’s edicts (that I will call the Mura ethos for reasons to be explained presently) and its deliberate manipulation – and of other social norms like it – by the Japanese state dates back to the Meiji era (1868-1912) at least. Let’s briefly consider each in turn.

The Mura Ethos.

Japan’s institutional debt to imperial China, says John Owen Haley, is difficult to overstate (Hayley 1991, p.19). As they began to exchange and interact more in the late 5th century, early Japan imported a number of things from imperial China, amongst which was a particular conception of the law. In this tradition, the law was seen as primarily an instrument of political control, serving the projects and interests of those in authority – namely, the emperor and his representatives.

It was understood that the emperor sat atop a social and cosmic hierarchy and he (rather than anything transcendent or deistic as in the European tradition of natural law) was the source of the law which he used to maintain harmony. Additionally, there was (and arguably is) no conception of private law (in which control over law is exercised by private parties) as opposed to public law (in which state officials exercise the control), meaning that there was, in principle, no limits, institutional or metaphysical, on the claims to authority that the emperor and his representatives in the state could make over people’s lives. It was, Haley says, “totalitarian in scope” (Haley 1991, p.27).

However, just because the administrative state was pervasive in theory, does not mean that it was always so in practice – or even that when it was, it acted coercively…

Writing from his Westerner’s perspective, Haley also describes Japan as a ‘paradox’. The Japanese state, he observes, appears to combine expansive strength in its reach into people’s lives with limp-wristed weakness in its ability to coercively enforce its edicts or laws. Describing socio-political norms in all but in name, he writes:

Japan is […] a society in which terms of authority to act and intervene, the jurisdictional mandate as it were, government or the state seems pervasive yet its capacity to coerce and compel is remarkably weak. The result is a dependence on extra-legal, informal mechanisms of social control as a means for maintaining societal order with a concomitant transfer of effective control over rules and norms that govern society to those who are able to manipulate these informal instruments of enforcement. [emphases mine] (Hayley 1991, p.14)

Frankly, this would only have been more prophetic if he’d concluded “…in response to a re-engineered sarbecovirus, leaked from the Wuhan Institute of Virology” as the Japanese state’s reliance on “extra-legal, informal mechanisms of social control” like jishuku showcased both its tentacular reach and its lack of hard power. Haley traces this ostensibly paradoxical situation’s origins back to the Edo period (1603 to 1867) when most of modern-day Japan lay in the dominion of the Tokugawa shogunate.

Superficially, Tokugawa Ieyasu’s ascension as Shogun represented a never-before-seen centralisation of political power in Japan. He stripped his enemies of their territories and re-distributed them amongst his allies, and, consistent with the principles of sinic administration, he and his successors introduced an expansive network of fiscal and civil regulations that dictated everything from who could alienate land to what sort of rain gear each could use (peasants were only permitted to wear straw hats and straw coats…) (Hayley 1991, p.55-57). Beneath the surface however, power remained far more diffuse and the most important unit of sociolegal organisation was the village, or mura, in which ~ 80% of the population lived (Hayley 1991, p.60) as, despite their volume and detail, an unfavourable mura-to-Tokugawa-official ratio meant that the shogunate’s regulations were often unenforced or unenforceable.

As a consequence, mura inhabitants enjoyed a sort of conditional autonomy from central authority – as long as their taxes were paid and they didn’t do anything to draw administrative scrutiny, they could live relatively free of outside interference. This, Haley argues, produced an ethos of “ritualised [outward] deference to authority” and methods of in-group policing that endure to this day (Hayley 1991, p.170). Villages knew that their relative freedom hinged on an outward appearance of collective peace and good behaviour, and so became very adept at internally regulating and suppressing conflict – that is, self-policing. And if conflict could not be resolved or an individual could not be trusted to behave, then disruptors were exiled in a punishment still known today as murahachibu, which was pretty severe at a time when each depended on their community for shelter and sustenance. “Community sanctions” clarifies Haley, “not the samurai’s sword were the real deterrents of wrongdoing in Tokugawa Japan” (Hayley 1991, p.61).

The mura ethos’ persistence has made it possible for the Japanese state to exercise enormous influence over its subjects, without necessarily having the hard power to impose its edicts that we Hobbesians imagine the Leviathan needing. It could emit instructions and trust that communities would self-police to achieve (the outward appearance of) compliance. This remained the case throughout the 20th Century and can still be seen in contemporary business practices as well as in the country’s response to COVID-19. Not for nothing does James Wright refer to the jishuku keisatsu’s activities as a modern day murahachibu (Wright 2021, p.467)!

The Deliberate Manipulation of Social norms by the Japanese State.

The sinicised administrative state and the mura ethos were amongst the socio-political pre-conditions that gave rise to a norm of Japanese statecraft known as kyōka, roughly translated by Sheldon Garron as ‘moral suasion’ (Garron 1998, p.7). It emerged in the second half of the 19th Century when, following the Meiji restoration, Japan’s newly installed bureaucrats realised that the country, in its quasi-feudal condition, could not hope to match an industrialised, acquisitive West and so was at risk of colonisation. In light of this, the Meiji bureaucrats launched an ambitious project of self-conscious nation-building, looking to western technologies and techniques for inspiration, and, in proper sinic fashion, conceiving of themselves as enlightened “shepherds of the people” (Garron 1998, p.16).

Unlike the West, however, the Meiji state did not primarily pursue its policy-aims through legal or infrastructural intervention but through extensive campaigns of moral ‘reform’ and ‘(re)education’, often aimed at mura and small towns (kyōka refers to these campaigns specifically). A nicely illustrative example of this was the ‘Japanese-style’ welfare program implemented by a legendary Home Ministry bureaucrat, Tomoichi Inoue. Both influenced by western Malthusianism and Fabianism, and presumably aware of the Tokugawan legacy of self-government and self-policing described before, Inoue launched a series of kyōka campaigns, aimed at fostering mutual assistance and thrift amongst the Japanese (Garron 1998, p.43).

Part of these campaigns was a 5-week course called the Reformatory and Relief works seminar, which local community leaders (assumedly including of the mura) were expected to attend to learn about how to undertake social work in their municipalities (Garron 1998, p.47). The content was driven by the conviction that local behaviour change and mutual assistance were better responses to poverty than state-funded relief, and it insisted that families and the local wealthy had an obligation to help their poor relatives or neighbours. Attendees were instructed in “methods of moral exhortation in order to prevent socialist thought, discourage dependency on material relief, and strengthen the family’s obligation to support its own” (Garron 1998, p.47). The first of these seminars was held in 1908 and over the course of the next fifteen years, twenty-eight more were given, outlasting the Meiji government.

Inoue himself proudly noted that ‘Japanese-style’ welfare relied less on legal or infrastructural interventions (although there was some of those, of course) than its western counterparts (Garron 1998, p.26). For example, the Meiji government did not introduce a minimum wage and actually reduced its already-miserly welfare-spending during Inoue’s kyōka campaigns (Garron 1998, p.42). Similarly, while family members and the rich were emphatically encouraged (and sometimes informally forced) to provide care and assistance to the needy, they were never legally obliged to do so like in some of the West’s poor laws. Instead, Inoue and the other bureaucrats relied on manipulating social norms and local communities’ ethos of self-policing to achieve their policy-objectives – once again, foreshadowing the weaponization of public morality and ‘voluntary’ behaviour changes in response to the COVID-19.

Bureaucratic attitudes to welfare spending aside, Japan was (and is) no laissez-faire paradise and the state intervened liberally into people’s lives. However, as the preference for ‘soft’ or extra-legal methods like kyōka and gyōsei reveal, this was (and remains!) intervention of a different sort to the one imagined by western Hobbesians. Japan, observes James Wright, is a society of ‘mood regulation’ (Wright 2021, p.465), where the state achieves its aims by instrumentalising (or negotiating with) social norms and customs (notably those of self-policing) rather than through legal or infrastructural intervention – in other words, by means of socio-political norms.

§ Beyond Mandates - Lockdowns as a Socio-Political norm.

Probably due to our latent Hobbesianism, Western critiques of the COVID-19 response have largely focussed on the role and damages of compelling behaviour. And justifiably so as the mandates’ inflexibility and tyrannical universality surely contributed to the lockdown’s harms. However, Japan also demonstrates how, under the right socio-political conditions, mandates are not necessary for the successful implementation of lockdown behaviours. As such, a critique of lockdowns that focusses on mandates alone is not sufficient for understanding (1) what makes a lockdown harmful and (2) what is needed to prevent them from ever happening again.

What makes a Lockdown harmful?

Because that is where they focus their critical zeal, western lockdown sceptics have often liked to imagine a pandemic response without mandates – one, that is, hinged on so-called ‘Voluntary Behaviour Change’ (VBC). Here is a nicely representative (if a bit arbitrarily chosen) account of this pandemic management strategy from Steven R. Kraaijeveld:

“…under a lockdown approach, citizens are compelled to act in ways that will collectively protect vulnerable others, while an altruistic approach [what Kraaijeveld calls the VBC strategy] allows citizens at least some freedom toward that end. This is an important difference between the two approaches, which is clearly relevant for any justification of the approaches from a public health ethics perspective.

[…]

Importantly, an altruistic approach does not mean that everything remains as it was before the outbreak of the virus; the guiding assumption in light of COVID-19 has been that governments do need to take some kind of action to curb the spread of the virus. An altruistic approach means that governments do proactively engage the public with regard to the importance of taking measures to flatten the curve, so as to protect vulnerable people and health care systems. Knowledge about the coronavirus and about the measures that can be taken against its spread needs to be disseminated among the public. In fact, for the approach to be properly altruistic in my sense of the term, and not simply a hands-off approach, governments have to stress precisely what citizens could and ought to do in order to flatten the curve and to help one another get through the pandemic.” (Kraaijeveld 2020, pp.201-202)

VBC’s poster-child has, inevitably, been Sweden. Ah, the Swedes – they, we are told, took a ‘relaxed’ approach to the pandemic, choosing to leave most schools, gyms, restaurants, and bars open, and eschewing mask- and vaccine-mandates, and have nonetheless enjoyed better-than-average pandemic outcomes. They are also likely to be spared the unfurling of lockdown harms over the coming years.

What this commentary misses, however, is that the Swedes do not really seem to have behaved in the way that VBC narratives suppose – i.e. they do not really seem to have adopted ‘curve flattening’ behaviours, voluntarily or otherwise. In his brief summary of Europe’s mobility data, Noah Carl notes that, Sweden saw the smallest cumulative percentage change in time spent at home in Spring 2020, out of the 33 countries listed (Carl 2023). And, when measuring changes in retail/recreational mobility for Spring 2020, Sweden is also consistently amongst the lowest – lower than all the countries that imposed mandatory lockdowns.

For its part, Japan experienced a greater drop in retail/recreational mobility than Sweden – though still smaller than countries with mandatory lockdowns like France, Spain, or the United Kingdom. However, its mobility in grocery shop/pharmacies (i.e. ‘essential’ purchases) remained quite similar to Sweden’s, suggesting that these changes were the result of jishuku-motivated, ‘voluntary’ behaviour changes. Furthermore, these mobility graphs do not reflect the widespread behaviour changes such as in interactions or mask-wearing, some of which I described above.

One particularly affecting example of Japanese ‘voluntary behaviour change’ that I did not describe above are the corona-mitigation policies implemented in Japanese schools. Though they remained out of class for only a short while, Japanese schools-kids were nonetheless subjected to all sorts of barbaric restrictions and rules5, many of which lasted into late 2022 long after schools had re-opened in the mandate-happy West (e.g. Japan Times 2022, Guardian 2022). For instance, alongside masking, Japanese children were also made to eat their school meals in complete silence, often all facing in the same direction and sometimes even partitioned, in a practice called mokushoku.

Though these policies were technically ‘voluntary’ and not mandated by the State6, they have nonetheless had some pretty dire consequences. Here’s one: Asahi Shimbun’s educational supplement recently published an interview with a psychologist, Masami Yamaguchi, during which she expressed concern about ‘mask dependency’ amongst the young Japanese (EduA 2022). Mask dependency is when people experience anxiety at the idea of showing their faces to others. It may even be a form of body dysmorphia, she says, as young people start to feel that their faces are too ugly to show to others. She also worries aloud that masks will have long term impacts on this generation’s social relations – not seeing your school-colleagues’ face reduces your chances of recognising them later in life, and so narrows the reach of your social web. In these and her other observations, she echoes the worries raised by pro-child activists across the West (Cole and Kingsley 2022 for e.g.).

Similarly, the Guardian recently reported that Japan now has around 1.5 million people living as complete social-recluses, or hikikomori, with around a fifth (20.6%) saying that they have been pushed into it by the COVID response (Guardian 2023). Based on back-of-the-envelope calculations, that is 309,000 people in a limbo of complete isolation from society, possibly in perpetuity, compared to 74,694 confirmed deaths (WHO COVID-19 dashboard). While there may have been more COVID deaths without jishuku, these hundreds of thousands of recluses are also likely just one tip of its collateral ice-berg of damage.

Obviously, my aim here is not to make a quantitative or exhaustive point about the harms suffered by the Japanese – for one thing, this post is already ~4000 words long. For another, I neither speak Japanese nor have the maths skills to do so. Instead, my ambitions are more modest. I just wanted to show that Japan (more than Sweden) did follow a VBC approach and has likely sustained a great deal of collateral as a consequence, and to use this to suggest that mandates are not the lone source of harm – the specific ‘curve-flattening’ behaviours (such as social distancing or masking) themselves are damaging, regardless of whether they are mandated or ‘voluntary’.

Put another way, it probably doesn’t make much of a difference to your kid whether you chose or were ordered to mask them – either way, they suffered the damages of wearing the thing for eight hours a day. Similarly, it probably ultimately didn’t matter to Granny whether her relatives were recommended to not or legally blocked from seeing her – again, either way, she suffered the indignities of abandonment. Narrowly focussing on mandates obscures this fact, as well as an implicit and difficult question: If ‘curve-flattening’ behaviours, both voluntary and mandated, are intrinsically harmful, then what should be done in the face of a wave of pandemic death? What actually matters in such a situation, and who decides? And how?

Preventing Future Lockdowns.

If our aim is to prohibit future lockdowns, then it cannot be enough to simply re-assert the inviolability of civil liberties and block mandates – Japan successfully locked-down without formally touching the former or imposing the latter! Instead, taking jishuku as a model, we urgently need to turn our gaze beyond the State and examine the analogous socio-cultural conditions that make future lockdowns plausible in the West. As a socio-political norm, jishuku was made possible by the widespread ethos of outward conformity to authority and a State able and willing to manipulate it. We need to ask if there are similar norms in our own countries, liable to play a similar role to the mura ethos.

Let’s consider the UK as an example. Though stay-at-home orders and mandates were widely used by Dominic Cumming’s, errr, Boris Johnson’s government, surveys conducted during the lockdowns suggest that people’s compliance was not primarily driven by a fear of legal coercion. Nor was it motivated by a personal fear of the illness (Jackson and Bradford 2021, p.2; Foad et al. 2021, p.7). Instead, it seems to have been much closer to jishuku in nature – people locked-down (often against their own interests) because a new idea of the ‘common good’ was introduced, one drawing on longstanding tropes in British political mythology such as protecting the NHS and the sacralisation of vulnerability (Ramsay 2022). Overnight, ‘good’ people became those who were willing to sacrifice their personal needs and projects to the NHS’ survival and understood that vulnerability to COVID-19 was our chief, perhaps only, national concern7.

Within this, the law actually had a similar function to Japan’s gyōsei – it expressed (rather than enforced) what was expected of British citizens by clarifying the ‘right’ or ‘moral’ thing. As such, people complied because they bought this ‘common good’ narrative, saw themselves as ‘good’ people, and did not want to be perceived as otherwise by their compatriots. They also complied because the law remains a symbolically powerful institution in Britain and enjoys a legitimacy that mere requests do not (Jackson and Bradford 2021, p.6).

At least up to now.

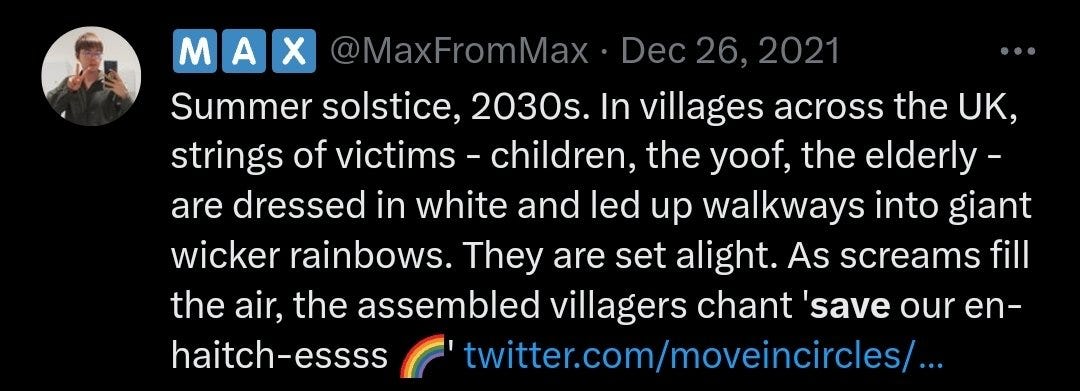

Despite what many lockdown sceptics think, I am not convinced that mandated lockdowns are set to return to Britain. They may just no longer be necessary. Lockdown-til-vaccine in 2020 may have been to Britain what Emperor Hirohito’s death was to Japan in 1989 – the crystallisation of a socio-political norm that will allow future British politicians to emulate Japan’s no-mandate lockdowns by appealing to ‘common good’ narratives akin to ‘Saving our NHS’8.

If this is true, then as I say, legal reform cannot be sufficient for preventing future lockdowns and we need to address the socio-cultural pre-conditions that make this exercise of power possible. While I am open to suggestions, I will end this never-ever-ending post with one of my own: fostering a social ethos of epistemic independence.

Not much can be done about the State’s awareness of social norms. For one thing, the state is often constituted by people born into those same norms and customs; for another, social-scientists and writers document them extensively; and, for one more, it is unclear that a State with zero awareness of how people live is preferable one with scores of it. However, something can maybe be done to the social norms themselves to make them resistant to or incompatible with instrumentalization by the State, thereby precluding an exercise of socio-political norms!

My suggestion here is that we foster a social ethos of epistemic independence.

By this, I mean that we should work towards a shared understanding that people are, in general, the best arbiters of what is good and right for them and their loved ones, even under situations of massive uncertainty like early 2020. To be clear, I am not suggesting that we do away with the very idea of epistemic authority, ‘scientific’ or otherwise – just that, as a default, we approach its claims to authority over matters pertaining to our lives with a degree of scepticism, and that we subsequently feel able to and comfortable contradicting it if something doesn’t seem right.

I’ll illustrate with the example of masking kids. It is well-known that over the course of 2020, advice on mask wearing flip-flopped wildly and even contradictorily. For example, in late February 2020, Dr Jerome Adams, the US Surgeon General, tweeted out:

But then, in early April 2020, this advice was reversed and, when schools re-opened that Summer, the CDC duly recommended that kids mask up (LA Times 2021) – for this example’s sake, let’s imagine that this recommendation never progressed to a mandate…

Now, I’d venture that it was always obvious to anyone with a conscience that masking kids for hours of the day carries serious implications for their well-being and socialisation and, accordingly, many mothers expressed concern over this policy (e.g. Cole and Kingsley 2022, pp.134-149). However, instead of being received with the honesty and respect that citizen engagement deserves, these expressions were met by opprobrium and disgust. They were accused of being ‘Karens’ or ‘granny-killers’, and of wishing sickness and death upon kids and teachers. Clearly, they had violated a core tenet of the US’ own stupefying ‘common good’ narrative.

In principle, this would not have happened under an ethos of epistemic independence. Instead, they – the mothers, that is – would have been accepted as the final authority on what is right and good for their kids and would have been left to determine whether masking was the right decision. They would also have been afforded the flexibility to revise their attitudes as their experience of the world changed.

In this way, they would have largely been insulated from the depredations of massifying ‘common good’ narratives like gaishutsu jishuku yōsei or SaveArrrEnnnAitchEsss. Though the pressure facing the health service may have informed their decision-making, it may equally have not, and they would not have been subjected to the same moral condemnations as the COVID-19 mums were. They may even have been celebrated! After all, under an ethic of epistemic individualism, coming to your own conclusions about what is right for yourself and your loved ones is the highest virtue, rather than the privilege or aberration it has been treated as in recent times.

In general then, we should aim for a Foucaultian turn away from the Hobbesian in our folk-understanding of political power and come to see how the State in conjunction with our peers, can act to shape our lives in pervasive and harmful ways. What jishuku reveals is that freedom from collective hysterias like lockdowns is not guaranteed by freedom from mandates and state coercion alone. It also requires a freedom from soft-power shenanigans and popular campaigns of stupid, homogenising moral messaging, as well as the ability to be the ultimate authority on what is right and good for you and your loved ones.

§ Bibliography.

Abe, M. (2016) ‘Sounding Against Nuclear Power in Post-3.11 Japan: Resonances of Silence and Chindon-ya’, Ethnomusicology, 60:2, 233–262.

Asahi Shimbun (2022) “素顔を見せたくない…増える「子どものマスク依存症」どうケアするべき?”, EduA, Retrieved from: https://www.asahi.com/edua/article/14788971?p=1

Borovoy, A. (2022) ‘The Burdens of Self-Restraint: Social measures and the Containment of COVID-19 in Japan’, The Asia-Pacific Journal, 20:19

Carl, N. (2023) “The myth of Sweden’s voluntary lockdown”, UnHerd, Retrieved from: https://unherd.com/thepost/the-myth-of-swedens-voluntary-lockdown/

Cole, L. and Kingsley, M. (2022) The Children's Inquiry United Kingdom: Pinter and Martin.

Foad et al. (2021) ‘The limitations of polling data in understanding public support for COVID-19 lockdown policies’, Royal Society Open Science, Retrieved from: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsos.210678

Garron, S. (1998) Molding Japanese Minds: The State in Everyday Life, Princeton: Princeton University Press

Guardian (2022) “Japanese pupils want end to Covid ban on lunchtime chatter”, The Guardian Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/nov/23/japanese-schoolchildren-end-covid-ban-lunchtime-chatter

Guardian (2023) “Japan says 1.5m people are living as recluses after Covid”, The Guardian Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/apr/03/japan-says-15-million-people-living-as-recluses-after-covid

Halliday, S. et al. (2022) “Why the UK complied with COVID-19 lockdown law” King's Law Journal, Vol 3., no .3, pp. 386-410.

Ijima, W. (2021), ‘Jishuku as a Japanese Way for Anti-COVID-19: Some Basic Reflections’, Historical Social Research, Supplement, 33, pp.284-285.

Jackson, J. and Bradford, B. (2021) “Us and Them: On the Motivational Force of Formal and Informal Lockdown Rules.” LSE Public Policy Review. Vol. 14, no 11, pp. 1–8

Japan Times (2020) ‘COVID-19 strategy: The Japan model’, Available at: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2020/04/28/commentary/japan-commentary/covid-19-strategy-japan-model/

L.A. Times (2021) ‘A timeline of the CDC’s advice on face masks’, Los Angeles Times Retrieved from: https://www.latimes.com/science/story/2021-07-27/timeline-cdc-mask-guidance-during-covid-19-pandemic

Mathieu, E. et al. (2020) "Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19)". Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus [Online Resource]

New York Times (2020) ‘Japan’s Virus Success Has Puzzled the World. Is Its Luck Running Out?’, Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/26/world/asia/japan-coronavirus.html

NHK (2022) “Masks off when the heat is on in Japan” NHK Retrieved at: https://www3.nhk.or.jp/nhkworld/en/news/backstories/2038/

NikkeiAsia (2023) “Masked Japan: 90% cover face 1 month after rules lifted” NikkeiAsia Retrieved from: https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Coronavirus/Masked-Japan-90-cover-face-1-month-after-rules-lifted

Hayley, J. O. (1991) Authority without Power. Cary: Oxford University Press

Ramsay, P (2022) ‘Vulnerability as Ideology’, The Northern Star, Retrieved from: https://thenorthernstar.online/analysis/vulnerability-as-ideology-i/

Repeta, L. (2020) “The Coronavirus and Japan’s Constitution” Japan Times, Retrieved from: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2020/04/14/commentary/japan-commentary/coronavirus-japans-constitution/

WHO (2023) ‘WHO Health Emergency Dashboard’ World Health Organisation, Retrieved from: https://covid19.who.int/region/wpro/country/jp

Wright, J. (2021) ‘Overcoming political distrust: the role of ‘self-restraint’ in Japan’s public health response to COVID-19’, Japan Forum, 33:4, 453-475

Beyond these narratives, the reality seems to have been quite different as, coercively enforced or not, lockdown behaviours seem to have been largely voluntary. See Jonathan Jackson and Ben Bradford (2021) “Us and Them: On the Motivational Force of Formal and Informal Lockdown Rules.” LSE Public Policy Review. Vol. 14, no 11, pp. 1–8 and Simon Halliday et al. (2022) “Why the UK complied with COVID-19 lockdown law” King's Law Journal, Vol 3., no .3, pp. 386-410. See also recent polling from UnHerd.

NOTE OF INTEREST: Borovoy (2022, p.16) gives us some idea of how far jishuku could reach into people’s lives when she writes,

…one article from 27 July 1939 recommends ‘jishuku’ summer hairstyles (jishukukata no natsu no kami) and illustrates an ‘easy-to-tie summer bun’ (tegaru na yuiage) which ‘anybody can do in five minutes’.

Wright also claims that Japan couldn’t do hard lockdowns-and-mandates for constitutional reasons (ironically, the post-WWII constitution was partially written by the now-mandate-happy USA…) but Lawrence Repeta (Japan Times, 14th April 2020) denies this, suggesting instead that the reasons political. Nonetheless, both agree that jishuku is a well-established norm of Japanese governance.

These explanations also resemble those found in nihonjinron literature, a reverse-Orientalist (or ‘Occidentalist’) Japanese genre focussed on trying to explain Japan’s successes in terms of its uniqueness or exceptionality. And much like nihonjinron texts, they play an ideological role in distorting or obscuring less-flattering aspects of the response that Japanese political elites would prefer were ignored. [See pp.12-14 of Kingston, J. (ed.) (2014) Critical Issues in Contemporary Japan, London; Routledge.]

Indeed, in his aforementioned Substack, GuyGin describes how the the Japanese government now claims that mokushoku was never official policy!

This was bolstered by appeals to something like a fetidly twee ‘Blitz’ spirit, not least in the late Queen’s “We will meet again” broadcast:

Note that the Chief Executive of the Government’s Nudge (i.e. Behavioural Science) unit, David Halpern said as much in a recent interview with The Telegraph. I’ll quote him liberally here:

Britain has been drilled to comply with lockdown under a future pandemic, the chief executive of the ‘nudge unit’ has said.

Professor David Halpern told The Telegraph that the country had “practised the drill” of wearing face masks and working from home and “could redo it” in a future crisis.

[…]

Speaking on the Lockdown Files podcast, the government adviser Prof Halpern predicted that the country would comply with another ‘stay at home’ order because they “kind of know what the drill is”.

I’d also like to clarify that I’m not suggesting the “Saving the NHS” narrative will be used in the future (although it might!). Public support for the NHS has waned (although support for its founding principles remains high!) and it may be the case that people will be less likely to sacrifice their own interests en masse to an ailing, inefficient system.